Cousin Sammy came to live with my grandparents in winter 1986. We were the same age, 11, and the oldest of all our cousins. Unlike the rest of my family, who were Chinese from the Philippines, Sammy was Chinese from mainland China. He spoke no English.

He was a pianist, the child prodigy kind. I marched through clunky sonatinas like a trained seal on my aunt’s upright Yamaha, but when I heard Sammy play, wearing a mustard yellow sweatsuit that my other cousins and I made fun of him for wearing, I realized I was only pretending to be a musician. Watching him whip through Mozart concertos by memory, his playing so expressive it made my grandmas cry, I’d feel a sharp envy in my fingers.

I smirked at his bowl haircut and his off-brand clothes, even though most of my own clothes were sewn by my mother; she cut my hair at our kitchen table. Sammy was not one of us, except of course, he was. My cousins and I called him Sandwich because he was chubby and when we asked him what his name was he replied in shaky English, My name is Sandwich because he didn’t know what a sandwich was, and when we laughed even harder he laughed along with us, and then I went back to my middle school where kids trailed me in the hallway making kung-fu shouts and gong noises.

In suburban New Jersey, we learned to renounce the parts of ourselves that seemed too unassimilated.

My immigrant parents were driven by American promises of respectability and education, the hope that a stable life could erase their collective history of instability. In suburban New Jersey, we learned to renounce the parts of ourselves that seemed too unassimilated, in the hope that if we erased accents and mispronunciations and disguised our homemade clothing, we’d be awarded with promotions, raises, a full acceptance into the middle class.

The last time I was told to go back to where I came from was in San Francisco, five years ago. The last time I was asked by a stranger if I spoke English was in New York City, earlier this year.

Last January, on the day of the US presidential inauguration, I watched Rogue One: A Star Wars Story in a movie theater in the Philippines. The audience rooted for the rebellion, the good guys fighting for freedom against evil and injustice. It’s an American story. My heart soared despite myself, a sucker for a cinematic crescendo. Afterward, my boyfriend and I sang Air Supply in a karaoke bar and ate cheeseburgers, sated. What exactly were the rebels rebelling against, anyway? I asked him. They’re just rebelling, he said.

America’s story begins with revolution, but only certain revolutions are heroic. History lessons praise the dumping of tea, riots, and protests against taxation without representation, Paul Revere galloping through the night. Violence and rebellion are the necessary means for independence. Yet other revolutions must be suppressed, blacklisted, surveilled, policed. In 1969, the FBI called the Black Panthers a terrorist organization, “the greatest threat to the internal security of the country.” There are patriots, and there are extremists. Everyone wants to be the rebel, but only some of us are terrorists.

In May, I published a novel about an undocumented Chinese immigrant who is separated from her son, a story inspired by real-life families who have been permanently fractured by US immigration policies. I won’t lie — I was nervous. I’m a daughter of middle-class immigrants who wrote a book about poor and working-class immigrant families. In talking to my readers, I’ve emphasized the importance of amplifying other peoples’ stories, not speaking for them. But I worried I wasn’t doing enough.

They want reassurance, comfort; they are shocked to learn how many immigrants have been detained and deported in recent years.

This past year, I’ve traveled around the country promoting my novel, visited cities and states I’d never been to before, talking to people I would have never met if I hadn’t published a book. I’ve spoken with Asian-American students who told me I was the first Asian author they’ve ever met. I’ve talked to all-white audiences eager to ask me questions. Is assimilation really so bad? Do Chinese-Americans still experience discrimination? They want reassurance, comfort; they are shocked to learn how many immigrants have been detained and deported in recent years. I thought things were getting better, they say. I tell them racist immigration policies that profit the prison system are nothing new, that they’re an integral element of American history. But part of me understands that need for reassurance.

In Texas, I walked out of a reading and into a group of white supremacists carrying assault rifles and Confederate flags, chanting “USA” as they marched down the streets of downtown Austin. They were “counterprotesters” who outnumbered anti-fascists who had organized a rally against the Trump administration. Later, when I examined a picture I had taken, I noticed that one man was looking me right in the eye. When I showed the picture to people who live in open-carry states, they said it was nothing new. For weeks, I had nightmares about hiding from men with guns.

America is a country of immigrants, I’ve heard repeatedly. But some Americans have ancestors who were abducted and trafficked here against their wills, while others have ancestors who were here before America itself. Solidarity also doesn’t mean flattening our experiences, assuming our experiences are alike and devoid of context, power, and history. News stories profile immigrants who are surgeons and scientists, as if exceptionalism is a requirement to be American. But exceptionalism has never protected most Americans. Who in America is allowed to be ordinary and who must prove their humanity, as if it wasn’t already a given?

Who in America is allowed to be ordinary and who must prove their humanity, as if it wasn’t already a given?

It’s been a year since the election. In the subway station, I see ads for American Made, starring Tom Cruise, and remember the times I have protested, indignant, I was born here, when told to go back to where I came from. Look at my degrees, my job as an editor, I’ve wanted to shout. Not only do I speak fluent English, I’m paid to correct other people’s English! Not only, not only. As if I could so easily distance and protect myself by upturning expectations. I’m not one of them.

Am I doing enough? Have I done enough? It can be easy to fool myself into thinking that I have always been one of the rebels.

In the midst of my book tour I thought of my cousin, the divisions and distances within my own family. How Sammy learned more English, got wise to our taunts, quit the piano. He went to junior high, then high school. Last I heard, he was back in China, married with two kids.

I quit the piano, too, a long time after.

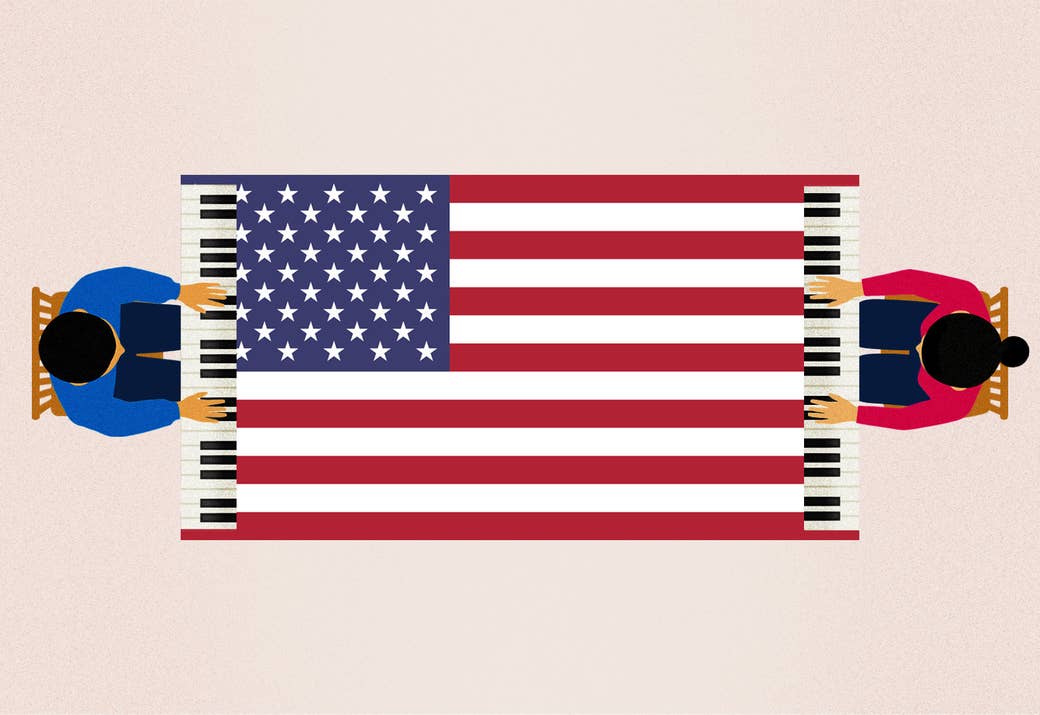

We played piano together a few times. In “Heart and Soul,” Sammy always let me take the high part, and when I would speed up like I inevitably did, unable to keep steady time, too impatient, he would match his part to mine, letting me have the fantasy that I was right all along.

There’s a thin line between the false promise of respectability politics — the myth of exceptionalism — and saying fuck it, it’s a fantasy, it’s a lie, let’s just be ourselves, let’s be loud and messy and talk shit about people in Cantonese while on line at the grocery store. Let’s steal the free bread at the restaurant and then ask the waiter for more to shovel into our purses, into the reused ziplock we brought just for that purpose. Let’s bring our own snacks to the movies and let them be shrimp chips and pork floss, let’s barter for a lower price at Sears and then pretend to not speak English. We did that and more and yet we believed it was okay to turn on the ones who had less, buying into the idea that there was only room for some of us. Like we weren’t the same, our survival dependent on one another, our spiked and complicated love. ●

Lisa Ko is the author of The Leavers, a novel that was a finalist for the 2017 National Book Award for Fiction and won the 2016 PEN/Bellwether Prize for Socially Engaged Fiction. Her writing has appeared in Best American Short Stories 2016, The New York Times, O. Magazine, and elsewhere. She has been awarded fellowships and residencies from the New York Foundation for the Arts, the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, and the MacDowell Colony, among others.